When author David Grann sought out the Osage tribe to tell the 100-year-old crime story behind Killers of the Flower Moon, it would have been understandable that Osage leaders would have been skeptical. After all, back when an endless supply of oil was found under tribe-owned land that left members the richest per-capita group in the country, their trust in their Oklahoma neighbors, local law enforcement and even their white spouses led to the Reign of Terror. That’s when as many as 100 or more Osage were shot, poisoned and otherwise killed, all for control of those oil lease payments.

The Osage remain a trusting people; they cooperated with Grann for the book, and Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Robert De Niro for the film bankrolled by Apple and just released globally. Already, Lily Gladstone, who grew up hearing stories of the Osage growing up on the Blackfeet Reservation, has the chance to go further in the Oscar race than any Native American before her, for her role as the film’s tragic moral center Mollie Burkhart.

For the Osage, renewed awareness of a largely unknown killing spree will have a profound impact on the tribe. That includes the removal of obstacles that will allow them to reclaim land and lease payment “headrights” that ended up outside tribal control. And it will free up current and future generations of Osage to discuss how so many of their heirs were killed so cruelly and callously.

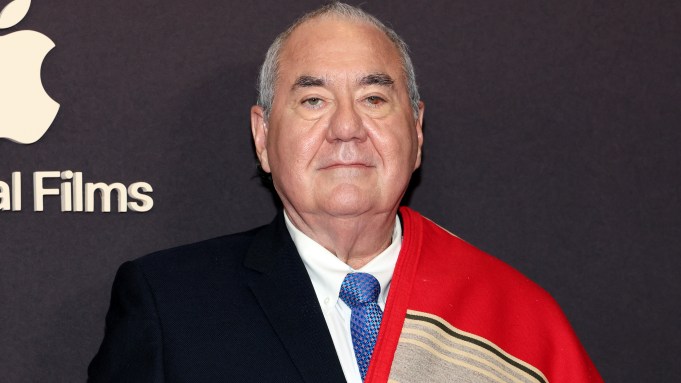

Here, Osage’s Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear describes the dividends that might come from trusting the right people this time.

DEADLINE: Killers of the Flower Moon opened globally and did solid business, and it will have a long tail with a berth on Apple TV+ around the holidays. This is a story of historical injustice most people don’t know. Having been through the process of the film taking shape over seven years, what’s the most gratifying thing about having the Osage’s story told?

CHIEF GEOFFREY STANDING BEAR: I like the word “process” that you use. That’s the word I use. David Grann was introduced to me 10 years ago by Kathryn Red Corn, an elder and director of our Osage museum at the time. She opened doors for David, who very respectfully interviewed elders who had kept documents and had good stories. This was a hundred years ago, but these elders were born during that time period, so they were not far removed. When the book rights were acquired by Imperative Entertainment [the company run by Dan Friedkin and Bradley Thomas], we became concerned. But after many discussions about what we wanted, what we expected, Imperative did tell us that they were going to make a movie the Osages will be proud of. They told us at a dinner we hosted here they were going to tell the story through the eyes of Mollie. The movie eventually went through its development and the business side of it, and we still didn’t receive assurances that the Osage language would be spoken even though it took place in the 1920s. In those days, our people were speaking it regularly, though it’s an endangered language now. We are working hard to carry it on.

We were concerned until the day, several years ago, that Marty Scorsese came to my office. The first thing he said after we were introduced to each other was, we will make the movie here. He said it with conviction. That immediately led to my offer to have his people work with our culture people on traditional clothing, traditional ways. And most importantly, I think with our language department here, what I find most gratifying is, as Marty says, not only were there so many Osages working as extras and in front of the camera, there were so many Osages working behind the camera.

That collaboration resulted in this movie. It went on for years, it was not just one event at one dinner, one conversation. It still goes on, this conversation, especially among our young people who not heard about it so much because my generation and my father’s generation just didn’t talk about it.

DEADLINE: Why?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: Even though my grandmother lived with us and my family growing up, and she was a translator for her father, she just wouldn’t talk about the murder part of it. She talked about driving the new blue Duesenberg vehicle, the new Buick Roadster, all the perks. It was just like someone talking about the land of Oz, all unbelievable to me. They became very insulated among each other. When that generation would get together at ceremonies or traditional dinners, they would talk exclusively in Osage. They would make sure that these were private conversations. I could pick up words here and there, so I knew they were talking about some person that walked in who I knew was from a family who was victimized. And remember there was a lot more than just … although the Hale murder ring was the worst and most notorious, there was a lot more. We don’t have an accurate number of how many deaths were not investigated, but it certainly gets close to a hundred.

DEADLINE: The complicity of the people assigning natural causes to highly suspicious deaths kept it a deep, dark secret?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: It wasn’t really a deep dark secret. People knew about it. We didn’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about it in our household. I’m married to an Osage and have Osage children, grandchildren, and I can tell you I’ve never talked about this in our household, until recently. It’s a true story. David Grann’s book shows that, and Marty Scorsese’s movie puts people and relationships into that story. I think that people will understand it is insane that someone could love someone else, while they’re killing their siblings and them. And what about her children? I bet I’ve heard people say that from that district over there that they believed Mollie actually loved Ernest. All the way until when she finally said, enough is enough and divorced him. She finally stood up at the end, and divorced him.

DEADLINE: History shows this happens, but it was depressing to imagine that people could be just so cruel to others, out of greed and a sense of entitlement. How did you hear the Osage were regarded by the people around them, who made their living off of them? Were they just looked at as people to exploit and overcharge, or were they accepted as neighbors for the most part?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: Well, no one’s asked me that. My observation is that the more headrights you had, the nicer people that were not Osage were to you and to your family. I was the oldest grandson, so I had a privileged position in culture, and my grandmother had received more than one headright. She owned that. She received that in 1906, and then she’s had some of her aunts, and I don’t know how they passed, but she was doing okay. But I noticed those Osage, which are now the majority, did not have a headright. They were treated with less respect. And I know I’m generalizing here, there were exceptions, but at the same time, there were restaurants here in the tribal capital that she could not go into, my grandmother. That no Osage could go into.

It was well understood, and you talk about the pricing. There was an Osage price until not too long ago. Cars, or the interest rates on loans, the guardianship system was set up by the state and federal government jointly and to be taken advantage of by lawyers and merchants and others. And that system just was insidious. The whole system of giving people numbers, whether you are going to be classified as a required guardian or not, just based on your blood quantum … when the government starts handing out numbers to you, you just be careful. And that continued until the year of my birth; 1953 to my knowledge, was the last year they issued role numbers. I’m number 4910, and after that, your ending card has your parents’ role number on it. And it’s just part of being classified not as an individual character or human, but as a number to fit into a line item, or a box, to be treated a certain way by the government and the merchants. And as you could tell, I put a lot of blame for this on the federal policies of the early 1900s and late 1800s, that created structures to destroy the communal property ownership of our lands into individual segments under control of individuals through the authority of the United States and the state of Oklahoma. That is proven by David’s book. The movie itself brings it to life as if you were there today. And it will make you angry when you see it, and it makes you think, and it can be depressing. That is correct.

DEADLINE: The indignity we see Mollie go through, having to sit before this bureaucrat whose job is to scrutinize why she needs money that belongs to her, after she has to first declare she is incompetent … it seems the height of degradation.

CHIEF GEOFFREY: And there’s a lot more detail, like the land partition laws. One rancher would acquire, maybe if there were five Osages owning 640 acres together, someone would acquire a weak member’s holding, or maybe someone passed away and they would acquire that interest. Then they would throw it under Oklahoma law allowed by federal law to apply into the partition system where the appraisals were low. And the money, your money as Osage, was held by the federal government. Depending on your oil royalties, and if you didn’t have enough money from your regular job, you couldn’t compete. And so a lot of land was legally acquired through the partition system where you could bid on the option that would be held on your land. And there’s a whole legal process, but it was popular like many other legal processes because the OS agents could not fully participate on equal footing.

DEADLINE: The result?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: It was inherently unfair but it was carried out, and it accomplished federal policy, which was to remove the property and wealth of the Native American, from the tribe as a whole and from the individual. And that policy still exists in so much continued federal government control. And if you try to remove it, they threaten you. They’ll say well, we’ll just make it taxable. And as one judge had told us young lawyers once, the power to tax is the power to destroy. So we know about these threats that if we are to seek true independence, there are negative consequences. Instead of supporting us, we find resistance.

DEADLINE: The movie’s creative development started with the Osage being killed, and then Hoover turns loose his stoic Texas Ranger lawman to clean up the town, like we’ve seen in many Westerns or films like Bonnie and Clyde. That procedural was why studios chased David Grann’s book. But Scorsese and DiCaprio decided Leo would be better off playing Ernest Burkhart, this man who was slowly poisoning his Osage wife. So Scorsese and Eric Roth rewrote the whole thing which better reflected reality because the bureau that became the FBI only got involved because the Osage’s desperate elders paid the government $20,000 to investigate. How relieved were you for the tribe you represent to not be fodder for another “white savior” movie?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: We were always on the lookout, which is why we were glad to hear Imperative tell us they were going to tell the story through the eyes of Mollie, and they were going to make a movie the Osage would be proud of. But as we went further, I still could not get the commitment about the Osage language, and they kept indicating they were trying to make that happen and they would try to film here. There the business end of this, with the state of Oklahoma film credit and competition with other states and that whole world, and we were watching it all carefully. And then when Marty said, we’re going to film here … one of the things we asked, and I asked him on behalf of my people at one of the early meetings, how are you going to approach this complicated story? And he said, I’m going to tell the story of trust and betrayal.

DEADLINE: How did he break that down?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: The trust the Osage people had of the outside world, and the betrayal of that trust. And on another level, the personal trust that Mollie had in Ernest and the horrible betrayal of that trust. And I just said, wow, that is a brilliant way to approach this complicated story.

DEADLINE: I saw an early cut in Marty’s office on a Friday, came back Monday for an interview and told him I had been depressed all weekend over how badly we can behave toward one another. When you saw the film, what was your reaction?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: Well, I saw it with my senior advisor, John Williams, sitting to my right and my language director Vann BigHorse sitting on my left. And Yancy Red Corn, who plays Chief Bonnicastle in the movie. And several ladies who helped Julie O’Keefe with costumes. Brandy Lemon, a member of our Osage legislature and Chad Renfro, my ambassador to the movie. We all were all in a private screening room. Leo DiCaprio sat behind us about three rows to the right, and Thelma [Schoonmaker, the film’s editor] is there. We watched that movie and when it was over, several people said, wow. For us, it was a wow moment. We began to discuss among ourselves right there, spontaneously. No one said, “Hey, now talk about it.” But we began to talk about it. I know a lot of the ladies said that scoundrel, basically Leonardo DiCaprio’s character Ernest. I said, well, you have to look at it. In my view, he was weak when he arrived. He had been injured in World War I. His uncle took him in and was able to offer him this refuge and a life. And the women said, the chief, no, there is no sympathy for this character. I was conflicted but I thought I’d best stay out of that discussion.

DEADLINE: You seem like a wise Chief…

CHIEF GEOFFREY: And others took [the conversation] over. Vann and I and Johnny Williams were very impressed with the use of the language and the culture, especially as Vann pointed out how Mollie and her sisters talked Osage conversationally to each other. And I heard Lily Gladstone talk about four months of working with our language people here. Same with Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and all the others. I’ve heard other people comment about how there’s no subtitles in a lot of this discussion that is all in Osage. And Marty will tell you, that’s because he didn’t want people to read the movie. He wanted people to watch the movie, I’ve heard him say. In those scenes, you could tell what they’re talking about.

DEADLINE: There is already scrutiny over how so many non-Osage, white people and institutions own headrights and land in Osage County. One hundred years have gone by, land has been passed one generation to the next, so even if as suspected the Osage in the movie got ripped off, it would be hard to claw it back after so long. What would you most like to achieve from the attention to what happened to the Osage, that would make it worthwhile when you welcomed in David Grann, and later Martin Scorsese, and trusted them with the telling of this historical injustice?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: Well, let me put it this way, from just my perspective as chief here, these last 10 years. And I was involved with my people before that. I’m looking at continuing what we were doing before David [Grann] arrived, which is acquiring and acquiring land that we had lost.

DEADLINE: How has that gone?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: We purchased 43,000 acres from Ted Turner, his companies for example. We have built a cattle herd, 2000 head of cattle. We have 250 head of bison. We have, as a result of the pandemic, invested in a 40,000-square-foot greenhouse, meat processing plant. We are building our nation. Now, what this movie and book does … I believe it has gotten a healthy discussion going. There’s anger, there’s pain, there’s a further commitment to some generational trauma, treatment, discussion, therapy. We are committing ourselves more to this. But beyond that, is the discussion of our younger people, the interests of our younger people in what little we have left here. Language, culture, land. Our territories, how we use it, how that generations that are growing up now will take this energy that has been tapped into, and use it creatively. And I’m just hoping and praying that they do their best to listen to the sayings of the ancient ones, and find what is important and how to go forward. That’s beyond my lifetime, but I think this movie has that historic an effect. It is not a story told by Hollywood about us. It’s us telling Hollywood.

DEADLINE: Leonardo DiCaprio said something to me that I thought was pretty profound, that you could get in a car from where the Reign of Terror happened, drive 30 miles and be where the Black Wall Street massacre happened in Tulsa in the same year. How do you process such a stunning thing?

CHIEF GEOFFREY: History is full of tragedy and horrible actions and we’re seeing that today. But you go back and your histories of the West and what Julius Caesar did in Gaul [after losing a battle against Celtic tribes, the Roman leader slaughtered 430,000 in the Celtic camp], that was pretty brutal. But it led to the Roman Empire and its principles, which to a great extent exists today in the western world.

DEADLINE: First thing Marty said in our interview was, he made this movie to show the evil that men are capable of and that we have to fight to rise above those instincts.

CHIEF GEOFFREY: You think of the Aztec Codex or the Mayan writings and how few survived. I was down in Mexico recently with Apple and Scorsese, and some of the journalists were telling me, this is a story we’re familiar with. And I said, what do you mean? They said, this happened to our native people too, and we’re glad to see this, because we can now start having this discussion. I think that’s what was intended by Marty and Apple, when I heard that Tim Cook said Apple wants to make movies that make a difference. And Marty, with his commitment to social justice .. .I’m just honored to be part of it.

Must Read Stories

Subscribe to Deadline Breaking News Alerts and keep your inbox happy.